Introduction

Sleep is essential for overall wellness, and emerging research highlights a significant connection between sleep and gut microbiota (Lin Z, 2024). Adequate sleep is crucial for growth, immune function, and overall health. Short sleep duration is associated with negative health outcomes, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and increased mortality (Osamu, 2017). Circadian rhythms, which are regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus, govern 24-hour biological processes, including metabolism and hormone release (e.g., serotonin and melatonin).

The gut microbiota also exhibits diurnal rhythms and interacts with these circadian processes, suggesting a bidirectional relationship between sleep, circadian rhythms, and microbial health. Peripheral clocks found in organs such as the liver and kidneys synchronize with the SCN but can be affected by feeding and fasting cycles. If these cycles become misaligned, it may lead to metabolic dysfunction (Matenchuk BA, 2020). Furthermore, sleep deprivation disrupts gut microbiota function, and sleep disorders are often associated with changes in gut microbiome composition (Wang et al., 2022).

In this paper, we will explore the bidirectional relationship between gut microbiota and sleep, examining the mechanisms involved and the therapeutic opportunities this presents. The gut-brain axis serves as a link for communication between gut microbiota and the central nervous system. Dysbiosis, the imbalance in bacterial composition, changes in bacterial metabolic activities, or changes in bacterial distribution within the gut microbiota, can impair sleep quality, and inadequate sleep can negatively impact gut health.

Sleep and Microbiota: A Historical Overview

Research on the relationship between the gut microbiome and sleep dates back to the 1960s when Pappenheimer and Karnovsky first investigated a sleep-inducing substance in the brains and cerebrospinal fluid of sleep-deprived animals (J.R. Pappenheimer, 1967). They discovered that this elusive substance was muramyl peptides (MPs), which are components of the cell walls of many bacterial species. Meanwhile, other researchers were examining how sleep deprivation affects the immune system, leading to a growing interest in the phenomenon of bacterial translocation across the gut barrier (C.A. Everson, 1993).

More recently, studies have focused on several key areas:

- The specific interactions between circadian rhythms and the gut microbiota

- The role of microbial alterations in the metabolic disturbances associated with shift work and short sleep

- The potential therapeutic effects of modulating gut microbiota to enhance sleep quality (Matenchuk BA, 2020)

Determinants of Microbiome - Early Life Exposures, Diet, and Stress

Microbial colonization and maturation of the gut occur during the postnatal period, continuing until approximately three years of age. This process establishes the foundation for the adult microbiome. The microbiome developed in early life significantly influences the host’s immune system and metabolism (Kozyrskyj, 2017).

Diet is arguably the biggest factor influencing the adult gut microbiome. Generally, diets that are rich in animal-based products increase the abundance of bile-tolerant organisms such as Alistipes spp., Bilophila spp., and Bacteroides, while decreasing the presence of taxa that metabolize polysaccharides. On the other hand, a higher intake of fiber and polysaccharides (types of carbohydrates) boosts the levels of beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium spp., Bacteroidetes, Akkermansia municiphila, Clostridium spp., and Prevotella spp. This shift contributes to improved gut barrier integrity, enhanced insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation, and better lipid metabolism (Cristina et al., 2017).

Activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis can influence the composition of the gut microbiota. Specifically, stress and HPA-axis activation have been linked to a decrease in the levels of lactobacilli species. Additionally, chronic stress disrupts the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Furthermore, research has shown that probiotic treatments in mice can reduce the baseline activity of the HPA axis and lower stress-induced levels of corticosterone (N. Sudo, 2017).

Gut Microbiota Influence on Sleep Physiology

Sleep is a complex biological process that influences various physiological functions. It is regulated by internal cycles and external factors, such as light exposure and feeding times (Logan, 2019). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is an endocrine pathway that plays a critical role in sleep regulation (Theresa M, 2005).

The human gut microbiota is a complex ecological network composed of bacteria, eukaryotes, Archaea, viruses, and phages. This community of microorganisms plays several vital roles, including protecting the host from pathogenic microbes, stimulating and modulating the host’s immune system, producing essential metabolites, and nourishing gastrointestinal cells. Interestingly, up to 60% of the total microbial composition fluctuates in a rhythmic manner.

Additionally, a large-scale functional network study of healthy young adults revealed that certain connections between brain networks mediated the relationships between microbial diversity, sleep quality, working memory, and attention (Huanhuan, 2021).

Microbial Species and Diurnal Microbiome Oscillations

The gut microbiome exhibits daily (diurnal) fluctuations in its composition and function, influenced by various factors, including host circadian rhythms. These rhythms encompass feeding-fasting cycles and sleep-wake patterns. Time-restricted eating has been shown to help stabilize microbial rhythms. Additionally, light exposure, as well as the rhythms of melatonin and cortisol, impact gut motility and microbial activity. Diurnal variations in these microbes may consequently influence mood. Certain bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bacteroides, exhibit time-of-day-dependent shifts in their abundance (Liang et al., 2015). Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are more prevalent during daytime feeding periods, contributing to mood stabilization (Zarrinpar et al., 2014).

Table 1: Bacterial Species Associated with Improved Mood and Sleep

| Bacterial Species | Psychological Benefit |

|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus | Reduces anxiety & depression, Improves poor sleep quality (GABA modulation) (Bravo et al., 2011) |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Lowers stress response (cortisol), improves mood (Messaoudi et al., 2011) |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Anti-inflammatory, protects against depression (Jiang et al., 2015) |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Enhances gut barrier, reduces neuroinflammation (Zhao et al., 2024) |

| Roseburia spp. | Butyrate producer supports cognitive function (Singh et al., 2023) |

In contrast, levels of Proteobacteria rise during sleep deprivation, which can lead to inflammation and depression (Benedict et al., 2016). Furthermore, the rhythms of Faecalibacterium are disrupted in shift workers who are experiencing depression (Rogers et al., 2021).

Table 2: Bacterial Species Linked to Psychological Risk

| Bacterial Species | Psychological Risk |

|---|---|

| Clostridium difficile | Anxiety, cognitive dysfunction (Rogers et al., 2016) |

| Escherichia coli (Proteobacteria) | Linked to depression & brain fog (Yun et al., 2020) |

| Ruminococcus gnavus, Fusobacterium, Escherichia-Shigella | Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Jiang et al., 2018) |

| Parabacteroides, Bacteroides, Weissella, and Halomonas | Bipolar Disorder and Depression (Hu et al., 2019) |

| Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Proteobacteria | Comorbid IBS and Anxiety/Depression (Kumar et al., 2023) |

Body Rhythms and the Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome exhibits dynamic, rhythmic fluctuations in composition and function over time, influenced by host circadian rhythms, diet, and environmental factors. This oscillatory behavior is critical for maintaining metabolic, immune, and neurological homeostasis.

Circadian Rhythm

The host’s circadian clock, which is regulated by genes such as CLOCK and BMAL1, influences gut motility, immune function, and nutrient availability, all of which shape microbial communities. Mice with disrupted circadian rhythms exhibit reduced diversity in their microbiomes and a loss of rhythmic bacterial taxa, such as Lactobacillus (Thaiss et al., 2016).

Shifts in Light-Dark Cycles Alter Gut Microbial Composition

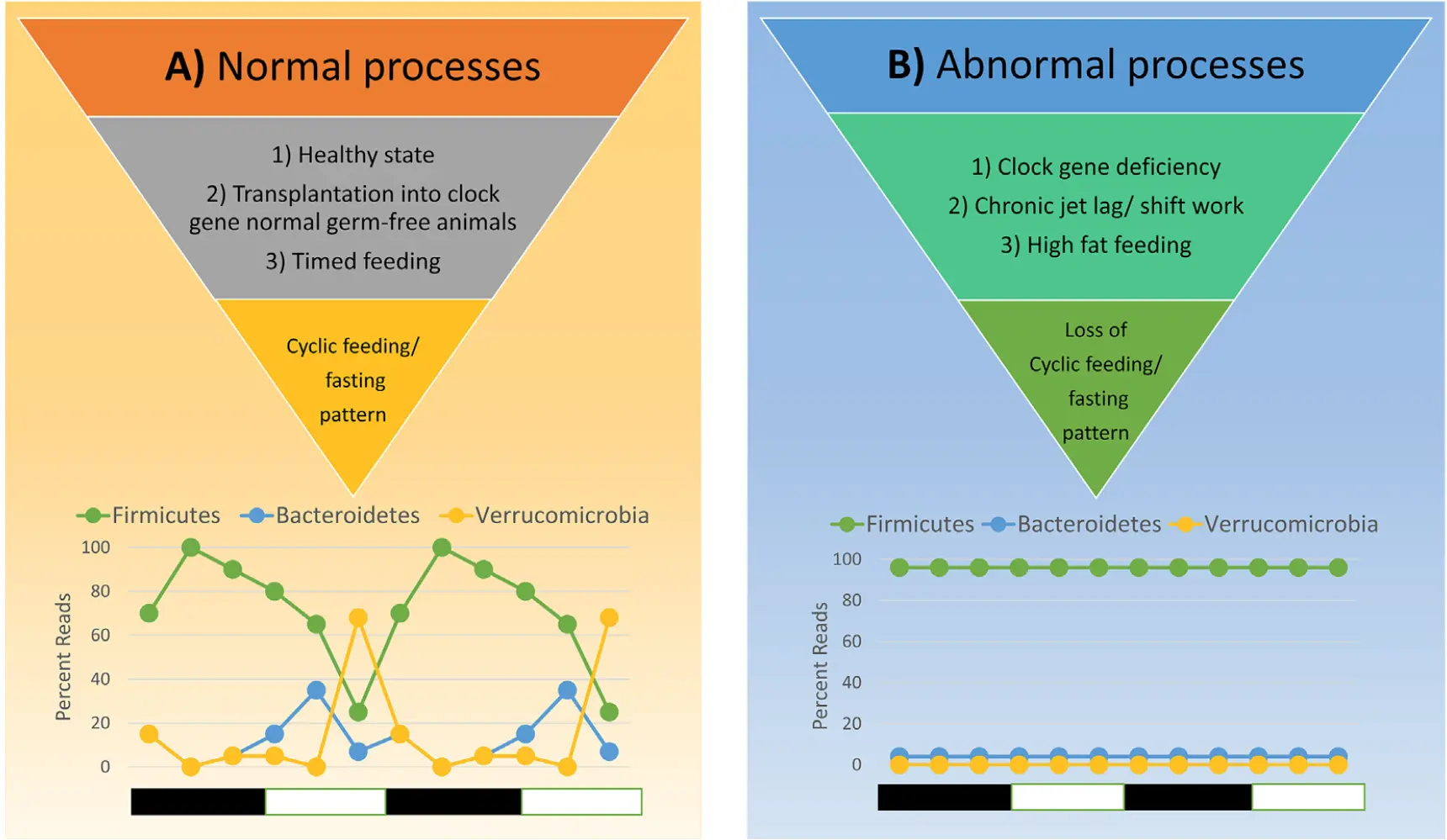

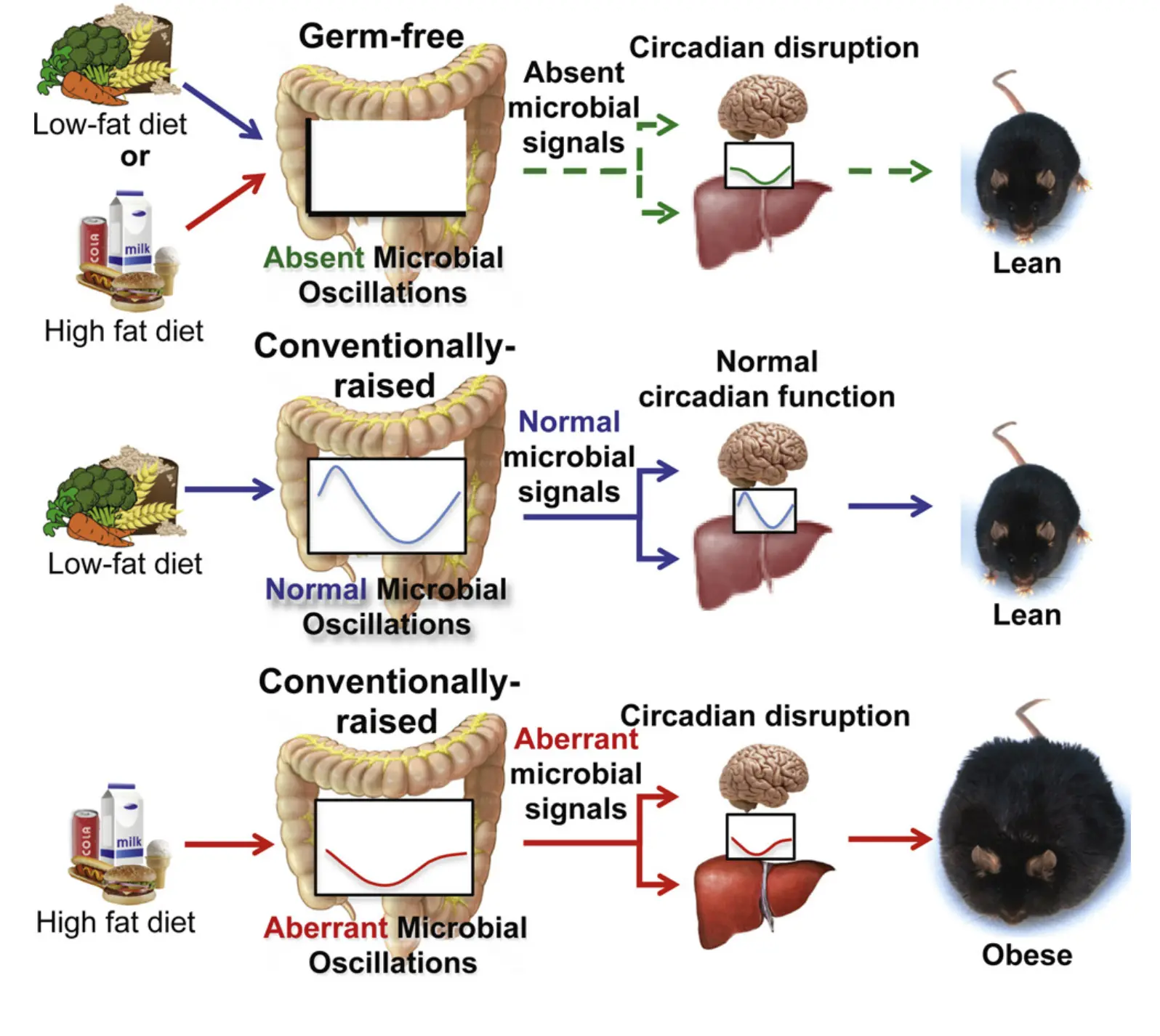

Research using a mouse model has demonstrated that the effects of circadian disruption, such as those caused by shift work or persistent jet lag, parallel the metabolic disturbances observed in humans with circadian disruptions. For example, persistent jet lag induced in adolescent mice, which involved an 8-hour shift in light-dark cycles every three days, led to significant changes in food intake rhythms and disrupted the rhythmicity and composition of their gut microbiota. This model of jet lag resulted in obesity and glucose intolerance.

Additionally, when microbiota from jet-lagged mice were transplanted into germ-free hosts, the recipients experienced weight gain and glucose intolerance, even while living under normal light-dark cycles. These findings provide evidence that external factors disrupting circadian rhythms can lead to gut dysbiosis in the host. In a study of two human subjects, the Firmicutes phylum of microbes became more abundant, while the Bacteroidetes were reduced in gut microbiota during a period of jet lag (one day after travel). Recovery from the dysbiotic effects of jet lag occurred within two weeks (Thaiss et al., 2014).

The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes Ratio

The Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio (F/B ratio) is a measure of the relative abundance of these two major phyla of bacteria in the gut microbiome. It’s often used as a potential indicator of gut health and is associated with various conditions like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and inflammation. A higher ratio (more Firmicutes, fewer Bacteroidetes) has been linked to obesity and other metabolic disorders, while a lower ratio has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A high-fiber diet tends to favor Bacteroidetes, while a diet high in processed foods and saturated fat may increase Firmicutes.

High-Fat Diet Dampens Microbial Rhythmicity

Dietary intake is closely linked to the composition of gut microbiota because the food we consume serves as the primary substrate for our microbes. Changes in our diet can lead to a complete reshaping of our gut microbiome within just a few days. High-fat diets disturb diurnal patterns of gut microbial structure and function. Disturbances of host-microbe circadian networks may promote diet-induced obesity (Leone et al., 2015).

In a study conducted in mice, feeding on a high-fat diet resulted in gut microbiota disturbance and aberrant microbial oscillations, dominated by species from the Firmicutes phylum (specifically Bacilli and Clostridia). However, time-restricted feeding helped restore the cycling of certain microbes, reduced the relative abundance of species associated with obesity, and increased the levels of microbial species that are thought to protect against obesity (Zarrinpar et al., 2014).

Figure 1: Homeostatic diurnal cycling of bacterial phyla for 48 hours in mice

Figure 1: Homeostatic diurnal cycling of bacterial phyla for 48 hours in mice

Clock Genes Control Gut Microbiota Composition

The circadian clock genes (e.g., CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY) not only govern the host’s sleep-wake cycle and metabolism but also directly modulate the composition and function of the gut microbiota.

Clock genes play a crucial role in regulating circadian rhythms, which are the 24-hour cycles of biological activity in organisms. These genes produce proteins that form feedback loops, controlling various physiological and behavioral processes. Although they are primarily active in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the brain, clock genes are also expressed throughout the body, influencing numerous cellular functions beyond just sleep-wake timing.

Additionally, microbial metabolite oscillations are associated with the host’s circadian rhythm and metabolism. Research shows that mice lacking the genes BMAL1 or CLOCK exhibit dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in Bacteroidetes and an increase in Firmicutes, which resembles metabolic syndrome (Leone et al., 2015).

Figure 2: Circadian Rhythm & Microbial Oscillations - showing how germ-free (GF) mice raised in completely sterile environments respond differently to diet

Figure 2: Circadian Rhythm & Microbial Oscillations - showing how germ-free (GF) mice raised in completely sterile environments respond differently to diet

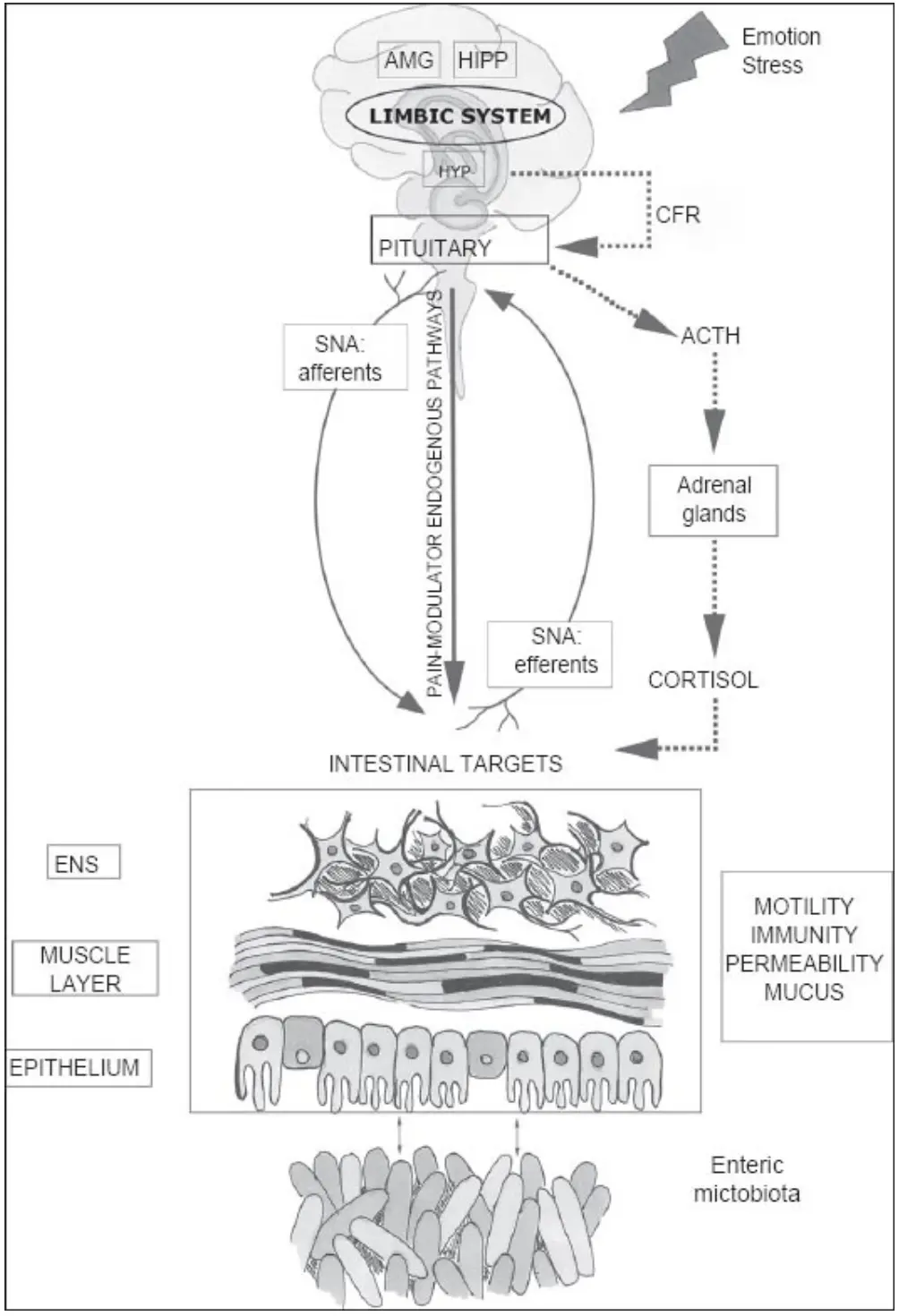

Mechanisms of the Brain-Gut Axis

The gut-brain axis involves interactions between the enteric microbiota and both the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS). This bidirectional communication links emotional and cognitive brain functions with intestinal activities, mediated through neural (via the vagus nerve), endocrine (HPA axis), immune, and humoral pathways. The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in influencing brain function and behavior, including the stress response, anxiety, and memory, while brain activity can also impact gut health. Dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, has been associated with various disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), autism, and anxiety or depression (Carabotti M et al., 2015).

The central nervous system, particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, can be activated in response to environmental factors like emotions or stress. This activation leads to cortisol release and is driven by complex interactions among the amygdala (AMG), hippocampus (HIPP), and hypothalamus (HYP), which together comprise the limbic system. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which stimulates the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland, ultimately resulting in cortisol release from the adrenal glands.

Simultaneously, the central nervous system communicates via both afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) autonomic pathways, with various intestinal targets, including the enteric nervous system (ENS), muscle layers, and gut mucosa. This communication modulates motility, immunity, permeability, and mucus secretion. The enteric microbiota engages in bidirectional communication with these intestinal targets, influencing gastrointestinal functions while also being regulated by brain-gut interactions (Carabotti M et al., 2015).

Figure 3: The Gut-Brain Axis Mechanism

Figure 3: The Gut-Brain Axis Mechanism

Vagal Pathways Involved in Sleep Regulation

The vagus nerve serves as a high-speed pathway for bidirectional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system (ENS). It extends from the brainstem (medulla) down to the abdomen, innervating the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. The vagus nerve consists of 80% afferent (sensory) fibers, which send gut signals to the brain, and 20% efferent (motor) fibers, which transmit brain signals to regulate gut function. This pathway also allows gut bacteria to communicate directly with the brain.

Research has shown that Lactobacillus rhamnosus can improve symptoms of depression and anxiety by modulating GABA receptor expression in the brain through a vagus nerve-dependent pathway (Bravo et al., 2011). Similarly, Lactobacillus reuteri has been found to improve social deficits in mice with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) through mechanisms that involve the vagus nerve, specifically mediated by oxytocinergic and dopaminergic signaling in the ventral tegmental area (Sgritta, 2019).

Moreover, serotonin receptors located on vagus nerve fibers may facilitate specific pathways in the CNS. Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) has demonstrated antidepressant-like effects that depend on the activity of these vagal fibers. Additionally, cats subjected to chronic vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) exhibited increased REM sleep (Valdes-Cruz et al., 2002).

Research by Breit et al. suggests that vagus nerve stimulation is a promising adjunctive treatment for conditions such as treatment-refractory depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and inflammatory bowel disease. Vagal tone is correlated with the ability to regulate stress responses and can be influenced by breathing techniques. Practices like meditation and yoga can enhance vagal tone, likely contributing to increased resilience and the reduction of mood and anxiety symptoms (Breit et al., 2018).

Endocrine Signals from the Gut Involved in Sleep Regulation

Melatonin

Melatonin (MT) is a hormone that plays a vital role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle. The two primary melatonin receptors, MT1 and MT2, mediate many of melatonin’s physiological effects, especially those related to sleep and the regulation of circadian rhythms.

Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland but is also produced by other organs such as the gut, skin, and bone marrow. Notably, after a meal, the level of melatonin produced in the gut can be up to 400 times higher than the amount secreted by the pineal gland. Recent studies have indicated that sleep deprivation disrupts the composition of gut microbiota and decreases melatonin levels in the plasma. Interestingly, supplementation with melatonin in sleep-deprived mice has been shown to improve the dysbiosis of the microbiota in the jejunum (the middle section of the small intestine) (Gao, T et al., 2020). Melatonin produced by the gut microbiota may influence sleep by acting on the MT1 and MT2 receptor signaling pathways in the brain (Wang et al., 2022).

GABA

GABA is an amino acid known for its role in promoting sleep. It also helps prevent anxiety, reduce stress, and stabilize mood. Many medications that target the GABAergic system are commonly used to treat insomnia. Research has shown that gut microbiota can influence GABA metabolism. For example, specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice have been found to have higher fecal levels of GABA compared to germ-free (GF) mice. A recent study revealed that Bifidobacterium adolescentis, which is isolated from the human gut, is capable of producing GABA. Gut microbiota, such as Limosilactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium breve, can improve sleep quality in stressed students. However, more direct evidence is needed to confirm the effects of GABA-producing bacteria on enhancing sleep and treating sleep disorders (Wang et al., 2022).

Serotonin

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) is a neurotransmitter that plays a crucial role in regulating mood, sleep, feeding, learning, and memory. It is primarily synthesized by enterochromaffin cells in the gut, with more than 90% of the body’s serotonin produced in this area. Some bacterial strains, such as those from the Clostridiaceae and Turicibacteraceae families, can also secrete serotonin. Recent studies have shown that Lactobacillus rhamnosus significantly increases serotonin levels in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of rats subjected to chronic unpredictable mild stress (Li H et al., 2019). These findings suggest a significant role for gut microbiota in serotonin secretion. Additionally, research by Yao et al. demonstrated that Ganoderma lucidum can enhance sleep and increase serotonin levels in the hypothalamus of mice (Yao et al., 2021).

Orexin

Orexin A is a neuropeptide found not only in the central nervous system (CNS) but also in various peripheral tissues in humans, such as the gut. Immunoreactive orexin A probes have shown that orexin A can be produced in the enteroendocrine cells of the mucosa in both the small intestine and the colon. Orexin A plays a critical role in regulating the sleep-wake cycle and food intake. The neuroreceptors for orexin A, OX1R and OX2R (which are G protein-coupled receptors), are widely distributed throughout the digestive system, including all regions of the human bowel and the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Clinical studies have demonstrated that the orexin receptor antagonist daridorexant can be effective in treating insomnia disorder (Dauvilliers Y et al., 2020). Peripheral orexin may influence sleep via the gut-brain axis.

Histamine

Histamine is a biogenic amine secreted by various types of cells. It plays a role in regulating immune function and the sleep-wake cycle through both central and peripheral pathways. Research has shown that bacteria in the gut microbiota can secrete histamine. Targeted knockout of histamine-producing strains in the gut may be beneficial for improving sleep (Wang et al., 2022).

Study on Microbiota Diversity Correlated with Sleep (Humans)

A study involving adult subjects found that greater diversity in the microbiome was positively associated with total sleep time (Smith RP, 2019).

The study investigated the relationship between gut microbiome composition, sleep quality, immune markers (specifically IL-6 and IL-1β), and cognitive performance in 26 healthy males. Sleep metrics, including efficiency and wake after sleep onset (WASO), were quantified over 30 days. Microbiome analysis was performed using 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples. Cognitive performance was assessed with tasks like abstract matching and psychomotor vigilance tests.

The research concluded that higher microbiome diversity correlated with better sleep efficiency, longer total sleep time, and less wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO). A balanced presence of specific bacterial phyla, namely Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, was linked to improved sleep metrics. Additionally, the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 was positively associated with microbiome diversity and total sleep time, suggesting a role in sleep regulation. The study found that microbiome diversity was connected to better performance on abstract thinking tasks, which are linked to prefrontal cortex function.

Overall, the study provides robust evidence that gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep quality, immune function, and cognitive performance, highlighting the potential for microbiome-based therapies for sleep disorders (Smith RP, 2019).

Sleep Disorders and Gut Microbiota

Recent studies have reported changes in gut microbiota composition in both patients with sleep disorders and animal models. Sleep disorders are increasingly linked to imbalances in gut microbiota, known as dysbiosis. The gut-brain axis, which is mediated by microbial metabolites, immune signaling, and the vagus nerve, plays a crucial role in this relationship.

Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by episodes of upper airway obstruction, leading to fragmented nighttime sleep and daytime sleepiness. Children with OSA syndrome (OSAS) show decreased microbiota diversity and increased inflammation levels compared to children without OSAS. Research suggests that there are elevated levels of intestinal inflammation in OSA cases (Valentini et al., 2020).

A study involving fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from OSA model mice demonstrated that this procedure can induce sleep disturbances in naïve mice (Badran et al., 2020). This indicates that the sleep-wake cycle may be affected by changes in gut microbiota associated with OSA.

Insomnia

Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder, increasingly impacting the health of a growing number of individuals. Liu et al. (2019) observed significant changes in gut microbiota diversity and composition among 10 chronic insomnia patients compared to 10 healthy controls. Similarly, Li et al. (2020) noted a reduction in microbiome diversity in both acute and chronic insomnia patients, with the most pronounced effects on bacterial diversity seen in those with chronic insomnia. Both studies suggested that an increase in the Bacteroidetes phylum could serve as a potential biomarker for identifying insomnia. They indicated that it might be feasible to differentiate between acute and chronic insomnia patients based on microbial differences (Li et al., 2020).

The gut microbiome could represent a novel target for treating insomnia. This condition may stem from a relative decrease in sleep-promoting neurochemical factors alongside an increase in wake-promoting neurochemical factors within the gut. Microorganisms that produce neurotransmitters related to sleep and wakefulness warrant further investigation in the context of insomnia. Research by Strandwitz et al. isolated various GABA-producing bacteria from human gut microbiota, finding that Bacteroides spp. could generate substantial amounts of GABA (Strandwitz et al., 2019).

Circadian Rhythm Disorders

Circadian rhythm disorders are a group of sleep disorders characterized by a misalignment between the sleep-wake cycle and the day-night cycle. Research indicates that circadian disruption decreases the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in individuals working night shifts. Additionally, the abundance of Faecalibacterium was noted in those working day shifts. Conversely, the genera Dorea longicatena and Dorea formicigenerans were found to be significantly more abundant in individuals on night shifts (Mortaş, H, 2020).

Sleep Disorders Comorbid with Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Numerous studies demonstrate that sleep disorders often co-occur with neuropsychiatric disorders, revealing distinct microbial characteristics in affected patients. It remains to be determined whether gut microbiota serves as a co-pathogenic factor in these comorbidities.

Zhang et al. discovered that the composition of gut microbiota is associated with sleep abnormalities in individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD). In this research, sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, depressive severity was evaluated with the Hamilton Depression Scale, and insomnia severity was assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index. Significant differences were found in 48 microbiota targets between patients with MDD and healthy controls.

In MDD patients, six microbiota targets correlated with the severity of depression, 11 with sleep quality, and three with the severity of insomnia. At the genus level, Dorea was linked to both depression and sleep quality, while Intestinibacter was more closely associated with sleep problems. Furthermore, Coprococcus and Intestinibacter were related to sleep quality, independent of depression severity. In conclusion, these findings enhance our understanding of the relationship between gut microbiota and symptoms related to MDD. Alterations in gut microbiota may serve as potential biomarkers or treatment targets for improving sleep quality in individuals with MDD (Zhang Q, 2021).

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently experience sleep problems. Studies have found a reduced abundance of Faecalibacterium and Agathobacter in individuals with ASD (Hua X et al., 2020). Additionally, analyses of fecal samples from ASD patients have shown decreased levels of melatonin and increased levels of tryptophan in those with sleep disorders, indicating that changes in neurotransmitter levels may be linked to their sleep difficulties (Hua X et al., 2020).

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder characterized by similar sleep issues. Both human and animal studies have confirmed the presence of sleep problems in AD patients. Furthermore, alterations to the bacterial flora can occur in individuals with AD (Hu X et al., 2016).

Microbiota-Targeted Interventions for Improving Sleep

Gut microbes are integral to maintaining mental health through the brain-gut axis. Various microbiota-targeted interventions, including probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), have demonstrated therapeutic effects in multiple conditions. Traditional sleep medications often come with numerous side effects, highlighting the urgent need for alternative strategies to treat sleep disorders. Microbiota-targeted therapies may emerge as promising novel approaches for managing sleep issues (Wang et al., 2022).

Probiotics

Probiotics are known as “good” or “friendly” bacteria because they help maintain a healthy balance of microorganisms in the gut, competing with harmful bacteria and aiding in digestion. Lin et al. isolated a specific strain of Lactobacillus fermentum (named PS150TM), which improved sleep in mice experiencing caffeine-induced sleep disturbances. Moreover, PS150TM increased non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep duration during a first-night effect in mice. Matsuda et al. reported that oral administration of ergothioneine, a metabolite of Lactobacillus reuteri, increased REM sleep duration in a rat model of depression (Wang, 2022).

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are a type of dietary fiber that serves as nourishment for beneficial gut bacteria, promoting their growth and activity. Research indicates that dietary prebiotics enhance NREM sleep by modulating specific gut microbiota metabolites in rats (Thompson et al., 2020). A double-blind randomized study demonstrated that early-life supplementation with a prebiotic blend extended nap latency and maintained daytime alertness in infants, effects mediated by alterations in gut microbiota (Colombo et al., 2021). These findings suggest that prebiotics may be effective for treating sleep disorders.

Synbiotics

Synbiotics refer to the combination of probiotics and their associated prebiotics. Sleep disturbances are common during military field training, leading to fatigue and sleepiness among soldiers. Valle et al. discovered that synbiotic ice cream helped mitigate feelings of sleepiness during such training, potentially linked to changes in melatonin metabolism in gut microbiota (Valle M, 2021).

Postbiotics

Postbiotics are non-living substances produced by bacteria during fermentation or metabolic byproducts that can benefit the host’s health. Nishida et al. found that administration of heat-inactivated Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 over 24 weeks significantly improved sleep disturbances in chronically stressed students. Compared to other microbial-targeted strategies, postbiotics are considered safer since they have no biological activity (Nishida K, 2019).

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Fecal microbiota transplantation, also known as fecal transplant or stool transplant, involves transferring stool from a healthy donor into a patient’s gastrointestinal tract to restore a healthy bacterial balance. A systematic review reported that FMT improved autism-related symptoms such as irritability, hyperactivity, and lethargy in patients with ASD (Tan Q et al., 2021). Kurokawa et al. suggested that sleep-related symptoms might improve with FMT in patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. A significant negative correlation was observed between baseline microbiota diversity and depression severity, and the increase in microbiota diversity following FMT correlated with improvements in depression scores (Kurokawa et al., 2018). However, optimal donor-recipient matching and the standardization of FMT procedures are still needed to ensure effectiveness and safety.

Conclusion

Currently, only a limited number of studies have examined gut microbiota alterations in relation to sleep mechanisms and sleep disorders associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. Additional research is required to clarify specific microbiota changes at the strain level and to elucidate the mechanisms linking these alterations to coexisting sleep and neuropsychiatric disorders. Future studies should also assess the efficacy of microbial-based therapies for insomnia, circadian rhythm misalignment, shift work, jet lag, and other sleep disorders.

References

Matenchuk BA, Mandhane PJ, Kozyrskyj AL. Sleep, circadian rhythm, and gut microbiota. Sleep Med Rev. 2020 Oct;53:101340. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101340.

Lin Z, Jiang T, Chen M, Ji X, Wang Y. Gut microbiota and sleep: Interaction mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Open Life Sci. 2024 Jul 18;19(1):20220910. doi: 10.1515/biol-2022-0910.

Osamu Itani, Maki Jike, Norio Watanabe, Yoshitaka Kaneita. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Medicine, Volume 32, 2017, Pages 246-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.006

Wang Z, Wang Z, Lu T, Chen W, Yan W, Yuan K, Shi L, Liu X, Zhou X, Shi J, Vitiello MV, Han Y, Lu L. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in sleep disorders. Sleep Med Rev. 2022 Oct;65:101691. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101691.

J.R. Pappenheimer, T.B. Miller, & C.A. Goodrich. Sleep-promoting effects of cerebrospinal fluid from sleep-deprived goats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 58(2) 513-517, (1967). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.58.2.513

C.A. Everson. Sustained sleep deprivation impairs host defense. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, Volume 265, 1993, Issue 5, Pages R1148-R1154. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.5.r1148

Wagner-Skacel J, Dalkner N, Moerkl S, Kreuzer K, Farzi A, Lackner S, Painold A, Reininghaus EZ, Butler MI, Bengesser S. Sleep and Microbiome in Psychiatric Diseases. Nutrients. 2020 Jul 23;12(8):2198. doi: 10.3390/nu12082198.

Logan RW, McClung CA. Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan. Nat Rev Neurosci 20, 49–65 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-018-0088-y

Theresa M. Buckley, Alan F. Schatzberg. On the Interactions of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis and Sleep: Normal HPA Axis Activity and Circadian Rhythm, Exemplary Sleep Disorders. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 90, Issue 5, 1 May 2005, Pages 3106–3114. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1056

Philip Strandwitz. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Research, Volume 1693, Part B, 2018, Pages 128-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.015

Smith RP, Easson C, Lyle SM, Kapoor R, Donnelly CP, Davidson EJ, et al. (2019). Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0222394. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222394

Huanhuan Cai, Chunli Wang, Yinfeng Qian, et al. Large-scale functional network connectivity mediates the associations of gut microbiota with sleep quality and executive functions. Human Brain Mapping, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25419

Kozyrskyj AL, Bridgman SL, & Tun MH. (2017). Chapter 4: The impact of birth and postnatal medical interventions on infant gut microbiota. In Microbiota in health and disease: from pregnancy to childhood. Wageningen Academic. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-839-1_4

Cristina Torres-Fuentes, Harriët Schellekens, Timothy G Dinan, John F Cryan. The microbiota–gut–brain axis in obesity. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Volume 2, Issue 10, 2017, Pages 747-756. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30147-4

N. Sudo. Chapter 13 - The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Gut Microbiota: A Target for Dietary Intervention? In The Gut-Brain Axis, Academic Press, 2016, Pages 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802304-4.00013-X

Thaiss CA, Levy M, Korem T, et al. Microbiota Diurnal Rhythmicity Programs Host Transcriptome Oscillations. Cell. 2016 Dec 1;167(6):1495-1510.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.003.

Christoph A. Thaiss, David Zeevi, Maayan Levy, et al. Transkingdom Control of Microbiota Diurnal Oscillations Promotes Metabolic Homeostasis. Cell, Volume 159, Issue 3, 2014, Pages 514-529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.048

Amir Zarrinpar, Amandine Chaix, Shibu Yooseph, Satchidananda Panda. Diet and Feeding Pattern Affect the Diurnal Dynamics of the Gut Microbiome. Cell Metabolism, Volume 20, Issue 6, 2014, Pages 1006-1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.008

Vanessa Leone, Sean M. Gibbons, Kristina Martinez, et al. Effects of Diurnal Variation of Gut Microbes and High-Fat Feeding on Host Circadian Clock Function and Metabolism. Cell Host & Microbe, Volume 17, Issue 5, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.006

Gao T, Wang Z, Cao J, et al. Melatonin attenuates microbiota dysbiosis of jejunum in short-term sleep deprived mice. J Microbiol. 58, 588–597 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-020-0094-4

Yao C, Wang Z, Jiang H, et al. Ganoderma lucidum promotes sleep through a gut microbiota-dependent and serotonin-involved pathway in mice. Sci Rep 11, 13660 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92913-6

Li H, Wang P, Huang L, Li P, Zhang D. Effects of regulating gut microbiota on the serotonin metabolism in the chronic unpredictable mild stress rat model. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019 Oct;31(10):e13677. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13677.

Dauvilliers Y, Zammit G, Fietze I, Mayleben D, Seboek Kinter D, Pain S, Hedner J. (2020). Daridorexant, a New Dual Orexin Receptor Antagonist to Treat Insomnia Disorder. Ann Neurol, 87: 347-356. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25680

Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G, Hasler G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 13;9:44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044.

J.A. Bravo, P. Forsythe, M.V. Chew, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108(38) 16050-16055, (2011). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102999108

Martina Sgritta, Sean W. Dooling, Shelly A. Buffington, et al. Mechanisms Underlying Microbial-Mediated Changes in Social Behavior in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuron, Volume 101, Issue 2, 2019, Pages 246-259.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.018

Alejandro Valdés-Cruz, Victor M Magdaleno-Madrigal, et al. Chronic stimulation of the cat vagus nerve: Effect on sleep and behavior. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, Volume 26, Issue 1, 2002, Pages 113-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-5846(01)00228-7

Mohammad Badran, Abdelnaby Khalyfa, Aaron Ericsson, David Gozal. Fecal microbiota transplantation from mice exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia elicits sleep disturbances in naïve mice. Experimental Neurology, Volume 334, 2020, 113439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113439

Francesco Valentini, Melania Evangelisti, et al. Gut microbiota composition in children with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: a pilot study. Sleep Medicine, Volume 76, 2020, Pages 140-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.10.017

Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015 Apr-Jun;28(2):203-209.

Liu B, Lin W, Chen S, et al. Gut Microbiota as an Objective Measurement for Auxiliary Diagnosis of Insomnia Disorder. Front Microbiol. 2019 Aug 13;10:1770. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01770.

Li Y, Zhang B, Zhou Y, et al. Gut Microbiota Changes and Their Relationship with Inflammation in Patients with Acute and Chronic Insomnia. Nat Sci Sleep. 2020;12:895-905. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S271927

Strandwitz P, Kim KH, Terekhova D, et al. GABA-modulating bacteria of the human gut microbiota. Nat Microbiol. 2019 Mar;4(3):396-403. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0307-3.

Hu X, Wang T, Jin F. Alzheimer’s disease and gut microbiota. Sci. China Life Sci. 59, 1006–1023 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-016-5083-9

Zhang Q, Yun Y, An H, Zhao W, Ma T, Wang Z, Yang F. Gut Microbiome Composition Associated With Major Depressive Disorder and Sleep Quality. Front Psychiatry. 2021 May 21;12:645045. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.645045.

Hua X, Zhu J, Yang T, et al. The Gut Microbiota and Associated Metabolites Are Altered in Sleep Disorder of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Sep 2;11:855. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00855.

Mortaş H, Bilici S, Karakan T. (2020). The circadian disruption of night work alters gut microbiota consistent with elevated risk for future metabolic and gastrointestinal pathology. Chronobiology International, 37(7), 1067–1081. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1778717

Tan Q, Orsso CE, Deehan EC, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of behavioral symptoms of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Autism Res. 2021 Sep;14(9):1820-1836. doi: 10.1002/aur.2560.

Shunya Kurokawa, Taishiro Kishimoto, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: An open-label observational study. Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 235, 2018, Pages 506-512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.038

Nishida K, Sawada D, Kuwano Y, Tanaka H, Rokutan K. (2019). Health Benefits of Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 Tablets in Young Adults Exposed to Chronic Stress: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients, 11(8), 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081859

Valle MCPR, Vieira IA, Fino LC, et al. Immune status, well-being and gut microbiota in military supplemented with synbiotic ice cream and submitted to field training: a randomised clinical trial. British Journal of Nutrition. 2021;126(12):1794-1808. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521000568

Colombo J, Carlson SE, Algarín C, et al. Developmental effects on sleep–wake patterns in infants receiving a cow’s milk-based infant formula with an added prebiotic blend: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr Res 89, 1222–1231 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-1044-x

Thompson RS, Vargas F, Dorrestein PC, et al. Dietary prebiotics alter novel microbial dependent fecal metabolites that improve sleep. Sci Rep 10, 3848 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60679-y

Liang X, Bushman FD, FitzGerald GA. Rhythmicity of the intestinal microbiota is regulated by gender and the host circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Aug 18;112(33):10479-84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501305112.

Benedict C, Vogel H, Jonas W, et al. Gut microbiota and glucometabolic alterations in response to recurrent partial sleep deprivation in normal-weight young individuals. Mol Metab. 2016 Oct 24;5(12):1175-1186. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.003.

Rogers A, Hu Y, Yue Y, et al. (2021). Shiftwork, functional bowel symptoms, and the microbiome. PeerJ. 9. e11406. 10.7717/peerj.11406.

Messaoudi M, Lalonde R, Violle N, et al. (2011). Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. British Journal of Nutrition, 105(5), 755–764. doi:10.1017/S0007114510004319

Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2015 Aug;48:186-94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016.

Zhao Y, Yang H, Wu P, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila: A promising probiotic against inflammation and metabolic disorders. Virulence. 2024 Dec;15(1):2375555. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2024.2375555.

Singh V, Lee G, Son H, et al. Butyrate producers, “The Sentinel of Gut”: Their intestinal significance with and beyond butyrate, and prospective use as microbial therapeutics. Front Microbiol. 2023 Jan 12;13:1103836. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1103836.

Rogers G, Keating D, Young R, et al. From gut dysbiosis to altered brain function and mental illness: mechanisms and pathways. Mol Psychiatry 21, 738–748 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.50

Yun SW, Kim JK, Lee KE, et al. (2020). A Probiotic Lactobacillus gasseri Alleviates Escherichia coli-Induced Cognitive Impairment and Depression in Mice by Regulating IL-1β Expression and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients, 12(11), 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113441

Jiang HY, Zhang X, Yu ZH, et al. Altered gut microbiota profile in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018 Sep;104:130-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.07.007.

Hu S, Li A, Huang T, et al. Gut Microbiota Changes in Patients with Bipolar Depression. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2019 May 15;6(14):1900752. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900752.

Kumar A, Pramanik J, Goyal N, et al. Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression: Unveiling the Relationships and Management Options. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Apr 9;16(4):565. doi: 10.3390/ph16040565.